Robinhood and His Merry Band

The Return of Active Investing

by Brian Sokolowski, CFA

Bluebird Wealth Management

Prior to founding Bluebird in 2018, I had spent the previous 14 years in investment research and portfolio management. A central function of the role was to attend a dozen or so investment conferences each year, which involved meeting with company management and discovering opportunities to actively invest client capital. I still attend these conferences, but upon founding Bluebird I decided to also attend a few conferences geared towards financial advisors and planners, to comprehensively add value to client relationships beyond active portfolio management. While I gained valuable insight in a few areas what jumped out most to me was a recurring theme in various presentations – the assertion that investment management is a commodity. Many of the presenters would urge the advisors in the audience to spend the bulk of their time cultivating relationships with other professionals; creating marketing initiatives; investing in various planning software; streamlining operations; sending Thanksgiving cards and pies; tiering clients by value, and more. Why waste time on investments, the theory goes. It is impossible to add value through investments, so why bother when you can simply outsource investment management at a low cost. Of course, most of those on stage had a vested interest in this line of thought, as they were attempting to sell the audience their (indexed) investment services to advisors, so we could focus on “the important stuff”. But this wasn’t the rogue theory of a few salespeople, it is unfortunately a belief held by a meaningful portion of both the financial advisory profession and the investing public.

How did we get here?

The success of a handful of mutual fund managers in the 1970s, with Fidelity’s Peter Lynch the most popular, provided an umbrella for the entire industry to charge high and rising fees for increasingly undifferentiated products. Excessive management fees, paired with 5-7% sales commissions (“loads”), on a group of increasingly similar products, created fertile ground for an innovator such as John Bogle to emerge and reshape the industry.

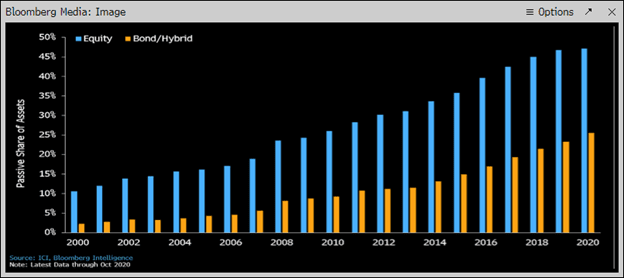

Mr. Bogle was the legendary founder of Vanguard, and pioneer of the index fund, a product designed to deliver a market average return, minus a modest fee, for everyone. Mr. Bogle’s success is evident in the $7 Trillion in assets overseen by Vanguard and, more importantly, in the impact he had on the industry and investor behavior over the last 40 years. “Passive” (investing according to a predetermined formula, often by tracking an index) has been gaining share over “Active” (investing according to a dynamic decision-making process, either human or machine) at a rapid pace for decades. According to ICI data, as measured by equity mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), the market share for Passive has increased from 10% in 2000 to 47% currently.

Passive share as % of Mutual Funds and ETFs (Bloomberg):

Mr. Bogle’s case is built on a logical foundation: the average mutual fund underperforms the market, after fees. The “market” is typically defined as the major index in a given country – the S&P 500 in the US, for example. Indexes are measured without fees, while mutual funds and ETFs (typically) carry fees. Therefore, comparing the average return from a universe of funds (with fees) versus an index (without fees) will result in the average fund underperforming index. Of course this math holds for a universe of index funds as well, a fact typically minimized in discussions around Passive and Active investing.

Mutual fund expenses have fallen significantly since the 1990s, and currently average 0.52% for equity mutual funds (both Passive and Active), or half the level of 1995. While Mr. Bogle’s logic was sound, and his efforts helped to drive a 50% reduction in mutual fund expense ratios to the benefit of investors (and almost-complete eradication of sales commissions), we would argue his lessons have been applied too broadly and often to the detriment of investors.

What does Passive really mean?

In practice, in how many circumstances does an investor have a chance to really act passively? Within a given asset class, there is some opportunity to be a passive investor, such as with a wide market US stock index. However, even within US stocks, there are often huge divergences, as illustrated by comparing the returns for the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the NASDAQ in 2020. The NASDAQ has returned almost 40% more than the Dow Jones in 2020. Further, very few investors are single asset-class investors. Most are choosing between stocks, bonds, cash, alternatives, hard assets and proxies, and more, and then further choosing between various subclasses, such as market capitalizations, styles, and sectors. There is a long list of decisions to be made, even for a “Passive” investor.

In the early 2000s, International equities outperformed US equities, which led to a surge in popularity of International stocks. International equity allocations found their way into institutional benchmarks, retirement plans, pensions, and investors’ portfolios. Many target-date funds, popular choices in retirement accounts, are allocated according to global equity benchmarks.

Let us compare the growth of two potential retirement portfolios over the last ten years: one allocated to a Passive equity fund tracking the major global equity index, the MSCI All-Country World Index, and the second allocated to a Passive equity fund tracking the S&P 500. The calculations are as of December 16, 2020 and do not include fees, for simplicity.

A $500,000 investment in the MSCI All-Country World beginning in December 2010, would be worth approximately $1,273,000 today (9.8% annualized returns). The same $500,000 invested in the S&P 500 Index would be worth $1,821,000 today (13.8% annualized returns), for a difference of more than 100% of the initial investment amount. The MSCI All-Country World Index currently includes a 55% allocation to US stocks, which prevented the ~4% annualized gap in returns from being even larger. The MSCI All-Country ex-US Index, with no US exposure, has trailed the S&P 500 by almost 10% per year over the last 10 years.

This example is not intended to make the argument that selecting non-US investments over the past ten years has been a mistake, as there have been many strong international stocks during that period. Rather, the example is to illustrate that a decision between two of the most popular ways for investors to gain Passive equity exposure can result in vastly different outcomes. We do not believe this decision can accurately be described as passive.

Perhaps the pendulum has swung too far?

There appears to be a nascent resurgence in Active investing, as more investors are unwilling to simply accept the average (or usually slightly below average, after index-fund fees) returns available to index fund investors. A visible example of this resurgence is the explosion of the electronic trading platform Robinhood, which has been driven (although not exclusively) by younger investors. Robinhood’s popularity is evident in its 13 million clients, and its meteoric rise to hold the number two position in retail trading volume. This is not a Robinhood-only trend, however, as peers (such as TD Ameritrade, Schwab, and Fidelity) are also experiencing strong growth in trading volume. Technological accessibility and low/no trading commissions have enabled this resurgence, but it appears that a wider change in mindset may be underway.

More data points indicating a return to Active investing include:

· While Passive equity market share of mutual funds and ETFs has grown from 10% to 47% over the last 20 years, and the rate of increase has been even steeper over the last 10 years at ~2.5% per year, the 0.7% rate of increase in 2020 has been the slowest rate of increase since 2013, and much slower than the ~2.5% annual rate over the last decade (source: ICI). This data indicates that within the world of listed equity funds (mutual and ETF), there has been a sharp slowdown in share gain for Passive in 2020. More importantly, confining the analysis to the parameters of listed funds is not telling the full story.

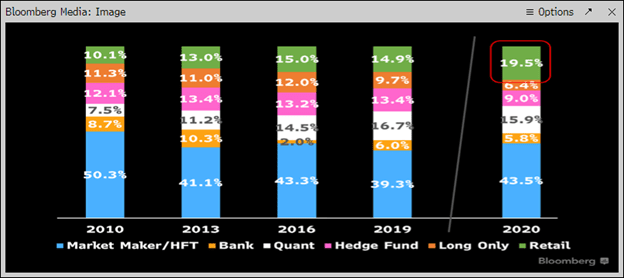

· Retail investors’ share of equity trading volume has doubled from 10% in 2010 to almost 20% in 2020, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. “Retail” is a bit of a misnomer, as it includes the trading activity of Registered Investment Advisors, such as Bluebird, who are managing portfolios on behalf of their clients. For example, the trades Bluebird executes while managing Separately Managed Accounts for our clients would be classified as Retail in this analysis. This activity is by-definition active investing.

“Retail” investors’ market share of equity order flow has almost doubled over the past ten years (Bloomberg)

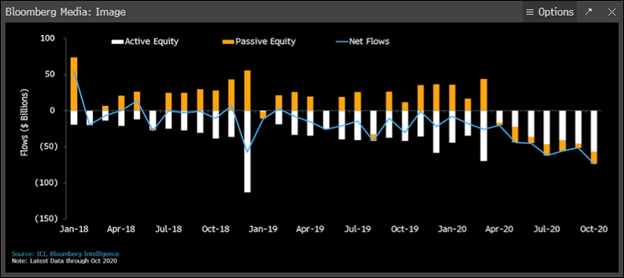

· While fund flows into Passive are slightly positive for the year, they are down each of the last 7 months (ending October), and down 60% from the 2019 level. Flows remain negative for Active as well. Where are these dollars going? The data indicates a significant portion of the assets are exiting the listed fund universe, and are responsible for the retail trading increase cited above. Unfortunately, there is also a meaningful amount which has been put into cash – a common (active) timing decision often made following equity market corrections, to the detriment of investors who then miss out on the market recoveries which typically follow.

Assets have exited Passive equity funds for 7 consecutive months (Bloomberg):

In conclusion, while we believe the characterization of “Passive” investing is often a misleading term, we are encouraged by a nascent move away from the more narrowly defined Passive investment approach. The sensible goal of fee reduction often results in unexpected results, as illustrated by the Global versus US allocation example above. Despite drawbacks, Passive has its merits and use cases, a characterization we cannot make for conference presenters arguing that investment management carries no value. There are countless investment philosophies, styles, and models. An investor should identify a robust and well-developed approach that fits their goals and style, because investment management is not a commodity.

Bluebird Wealth Management, LLC

Metrowest Office

(508) 359-4349

266 Main St.

Suite 19B

Medfield, MA 02052

North Shore Office

(978) 775-1287

12 Oakland St.

Suite 308

Amesbury, MA 01913

We serve individuals and families throughout the United States.

Bluebird Wealth Management, LLC

Metrowest Office

266 Main St.

Suite 19B

Medfield, MA 02052

+1 (508) 359-4349

info@bluebirdwealthmanagement.com

North Shore Office

12 Oakland St.

Suite 308

Amesbury, MA 01913

+1 (978) 775-1287

info@bluebirdwealthmanagement.com

We serve individuals and families throughout the United States.